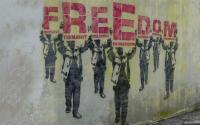

Warlords. They have a bad name but not all they do is bad. Their basic premise is that a good gun is better than a good law. Then there is the horsetrading: you give me oil, I will get you aid for Aids treatment; horsetrading can work when bureaucrats fail. Some warlords are grubby, others are imperial: as in Liberia, the warlord can descend from the heavens and declare it's time for the old order to go. Then there is the domestic warlord: the cowboy or the caudillo, always riding something - a horse, a tank - to an unknown destination.

Although warlordism is not new, it has had to adjust to new settings, like international treaties and whatnot. And it has had to become far more complex and indirect in its horsetrading. Bush is becoming a warlord who can handle it all. Two cases come to mind. One is the current visit to Africa, where Bush wants access to oil and the installation of US military bases and troops to make the region secure against terrorism. The second is the Bush administration's handling of the World Trade Organisation Doha declaration giving poor countries the right to override pharmaceutical patents in public health emergencies.

At the top of the list for horsetrading in Africa are oil and military bases or, at the least, troop stations. In return, Bush is offering aid for Aids victims and enhanced access to US markets. This is horsetrading at its best. The fine print on the offer of US market access has some notable features: the benefits for African producers are actually neutralised by the distortions resulting from US government subsidies to its farmers; these subsidies are larger than many African economies, and they are three times as large as total US aid to Africa as a whole.

US investment in oil production is being presented as a tool for development. This is not the first time this has happened, so we have some evidence on the matter. Again, the fine print does not look as good as the headlines. Oil has been a devastating fact for development in Africa: it has concentrated wealth and produced disincentives for any other type of development. Nor has it helped democracy, since entrenched elites lose much more than office if they lose control over the government. The economic shadow effect of oil is largely negative, and it all winds up creating more poverty. Oil-rich Nigeria and its 100m poor are exhibit number one.

What does the US get out of it? Today the US relies on Africa for 15% of its oil imports. The estimates are that by 2005 this will rise to between 20% and 25% of US oil imports. To this we should add the high quality of some of the African oil and the better transport distance from the Atlantic coast compared to the Middle East. Finally, if the US can also set up military bases and station troops to make sure everything is quiet, even if not peaceful, then we have a nice military-economic linkage.

One might say that Africa is special - that is, especially vulnerable - when it is horsetrading with imperial warlords. But we see similarly crafted fine print if we go digging into some of the WTO agreements that supposedly are victories for the interests of people in the global south. It also tells us something about why aid for Aids might be the one item in the horsetrading that might actually bring benefits to Africa - and it has nothing to do with the noblesse oblige of imperial warlords.

Every time countries of the global south have politically organised to see some of their interests reflected in the WTO declarations, the work of elaborating the details takes a peculiar turn. Sheer power trumps politics. The only time that politics can trump sheer power is when larger sectors of global civil society get involved in the fray, and do so with very well-defined goals in mind. Dissecting the case of the WTO Doha declaration illuminates each of these issues.

Global south countries did organise themselves effectively at the Doha meetings to resist some of the more damaging resolutions proposed by the global north. They succeeded in introducing the notion of options to override patents on pharmaceuticals. In the context of WTO and intellectual property rights this is almost subversive of global capitalism and "morally" wrong because it will damage the public collective interest of both poor and rich in supporting costly research. This was an important victory, especially since countries such as Brazil, India and Jordan have formidable pharmaceutical capabilities and are able generically to produce many of the drugs now under patent.

There was a second victory for the global south at the meeting. The WTO recognised that some of the poorer countries lack the resources to produce these medicines. Paragraph 6 of the Doha declaration is quite clear on this. These were the headlines.

But the horsetrading started soon after. the WTO designed a list of "approved diseases" that justify overriding patents on pharmaceuticals crucial for countries lacking the capabilities for generic production. The list turns out to exclude just about all major diseases for which the global north firms have developed medicines. Left on the list are mostly diseases for which these firms have not - one is tempted to insert "bothered to" - develop medicines or for which treatment is so old as to be off-patent. Dr Mary Moran of Médicins Sans Frontières reports that almost all of the major causes of mortality and morbidity in Africa for which patented western drugs exist have been excluded from the list of drugs poor countries can acquire outside the intellectual property rights framework.

There is one exception to these defeats: drugs for treating HIV/Aids. There are two important political lessons to be learnt from this case. Worldwide NGO mobilisation played a crucial role in making the large pharmaceuticals desist in their efforts to prevent poor countries from importing the far cheaper generically produced HIV/Aids drugs. What matters politically is that global protests by civil society helped poor countries get what they needed from the most powerful countries in the WTO: overriding the patents of Aids treatments held by the most powerful corporations in the world. This success is particularly significant as it is one of the few serious diseases that were not eliminated from the list.

The second lesson is that warlords will not simply leave it at this. The latest war the US is now preparing is a major attack on the WTO itself: they don't want it any more. Another attack is targeted against "progressive" NGOs and their growing influence. Two components illustrate the matter. The American Enterprise Institute, an influential thinktank closely associated with the Bush administration, launched the attack with a conference in Washington co-sponsored by the Australian rightwing thinktank, the Institute of Public Affairs. At least 42 senior representatives of the Bush administration attended. Secondly, the US Agency for International Development is now moving to grant more contracts to private firms instead of NGOs.

Warlords can go along with laws and international treaties if these do not interfere. When they do interfere, the horsetrading begins. And when this is not enough, well, there are always those guns.

Saskia Sassen is professor of sociology at the London School of Economics and the author of Guests and Aliens